The Rowan Art Gallery will host a celebration of the endurance and strength of the female form in art and architecture from Sept. 5 through Oct. 28. Virginia Maksymowicz is a gifted artist, and “The Lightness of Bearing” is a collection of her paintings that challenge us to consider the ongoing relevance of women throughout history. This exhibition is more than just a display of artwork; it is a thorough investigation of the historical contributions made by women, from the ancient caryatids to modern indigenous and ethnic cultures.

Born in Brooklyn in 1952 and now residing in Philadelphia, Virginia Maksymowicz’s journey in the world of art began with a B.A. in Fine Arts from Brooklyn College of the City University of New York in 1973 and culminated with an M.F.A. in Visual Arts from the University of California, San Diego in 1977. Her wide educational background and artistic vision have produced a collection of work that questions conventional ideas about the depiction and role of women.

“The Garden of Earthly Delights” is one of the exhibition’s highlights. This artwork evokes the decorative stucco interior designs reminiscent of eighteenth-century Neo-Classicism. Maksymowicz incorporates women’s heads with closed eyelids and a piece of fruit or vegetable gagged over them into the meticulously made wreaths. Words with various connotations like “ripe,” “firm,” and “luscious” are engraved beneath each picture. It’s interesting to note that Maksymowicz, with the help of her husband, made molds of her face, meticulously casting them into cotton paper pulp and painting them with acrylic.

“What sort of happens is for an artist’s career, there’s usually certain constancies, so for me, it’s sort of been the female figure. And part of it is because I am a woman. Part of it is because I’m always available,” said Maksymowicz, “So if I need a model, I can use myself. I can use my body or my face, or maybe just my hands or whatever. And then you start thinking about metaphors connected to that.”

Next, “Bearers” and “Mascarons” investigate the complex relationship between the human body and architecture. Drawings from Maksymowicz’s extensive travels, where she uncovered recurrent themes of significant women throughout history, including the Egyptian deity Isis and the Greek deity Demeter, are included in the exhibition “Bearers”. These illustrations show the pervasive importance of women throughout all cultures and regions.

On the other hand, “Mascarons,” is a series of twelve charcoal-pencil drawings. The name means “big mask” in architectural terms, revealing ornamental faces adorning building facades. Maksymowicz’s perspective on these faces is refreshing; instead of being menacing, she sees them as protectors. She discovered these faces in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and, upon speaking to a historian, learned that these faces represent the builders and architects, as well as their daughters and their wives. During the COVID lockdown, Maksymowicz drew these faces, adding a contemporary twist to this historical architectural feature.

When a printer for Maksymowicz’s spouse — also an artist — accidentally printed one of his photos on silk rather than on paper, the idea for the artwork called “Comparisons” was born. The artwork comprises seven pairs of lengthy silk banners that have had photographic pictures digitally printed on them, some of which overlap like double exposures.

Each banner’s fading pictures connect women in architecture and the arts. The exhibit requires viewers to actively participate by wandering around to recognize matched pictures and discover their connections and commonalities. This piece challenges its viewers to consider the mutually beneficial relationship that exists between women and the institutions they occupy and create.

“I like the Lightness of Bearing as the name for the exhibition because you might have heard a famous book called The Incredible Lightness of Being. And even though I confess that I haven’t read the book, it sort of posits that so much in life, repeats itself and occurs again over and over in different places and at different times,” said Maksymowicz, “And that kind of fits in with the exhibition. And then with the bearing, a lot of my work deals with women’s bodies and architecture.”

“Caryatids In Five Books” consists of five open volumes made of Hydrostone, each of which has part of a poem by Cristina-Monica Moldoveanu and a caryatid picture from Maksymowicz’s photo collection. The poems eloquently tell the story of a small child who makes a chalk doll that survives the erasing of math lessons on a blackboard. This piece of art also highlights the patriarchal culture that commodified women’s bodies as decorative elements for buildings, as well as the male sculptors who produced these figures.

“Zhyttya” offers simplicity and tranquillity in contrast to the intricacy of the other works. It resembles a portion of a Classical column since it is made up of three stacked basins decorated with acanthus leaf designs. The lower basins are filled with stones, pebbles, and wheat, while the top basin is filled with grain and has wheat “growing” from it, almost like a crown. Although the work does not specifically mention women by name, the Ukrainian phrase “Zhyttya,” which means “life,” represents the ubiquitous function of women in home cooking, raising families, and maintaining life.

Five Corinthian capitals are piled to make a column in the distinctive “Panis Angelicus” configuration, with the fifth capital turned upside down to resemble a basket for bread. The column is surrounded by loaves of bread, the piece makes a comparison between women carrying bread during festive occasions and how it is portrayed in “Comparisons.” The bread loaves at the base are intricately entwined with tiny figures of seraphim and cherubim. Maksymowicz enlisted the help of a select few random Rowan students who were given free rein to assemble the hundreds of individual components in any way they pleased.

Last but not least, “The Architecture of Memory” pays a moving tribute to the university itself. This installation incorporates casts of architectural molding from one of Hollybush’s rooms, preserving the memory of Josephine Allen Whitney, who gave birth to seven children in the house. The piece emphasizes the importance of women’s responsibilities in influencing not only families but also a wider cultural environment.

Not much is known about Josephine, quite frankly little to nothing is known about her and what is known is hard to find. Her history is broken — its pieces, scattered — which is what “The Architecture of Memory” is supposed to represent. It offers a quiet yet profound reflection on the power of memory and the women often overlooked by history. Josephine Allen Whitney is a great example of such a thing. With such little history and information about her, it fits into a single-frame place within the art piece.

“One of the students in the opening asked me an excellent question because it stopped me for a minute because I hadn’t thought of that. She said Why isn’t anything broken? Why isn’t it smashed? I answered and said if it’s too broken up, it’s hopeless. You can’t piece it together. So maybe I wasn’t thinking this through logically, but I think I was drawn to having sort of perfect pieces.”

The works of Virginia Maksymowicz, which range from the ancient caryatids to modern indigenous cultures, provide a potent reflection on the various roles that women play. We are reminded of the historical significance of women and their capacity to carry the burden of tradition, culture, and memory as we get fully immersed in these works of art.

This display forces us to reconsider our assumptions and recognize the significant contributions made by women in creating our world. Don’t miss the opportunity to experience this exhibition at the Rowan Art Gallery from Sept. 5th to Oct. 28th.

For questions/comments about this story email the.whit.arts@gmail.com or DM us on Instagram @thewhitatrowan.

![“[It’s] very low stakes. There's no auditioning; we rarely make cuts, you know. It's very welcoming,” Duffy said. - Multimedia Editor / Matthew Millroy](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IMG_2612.jpg)

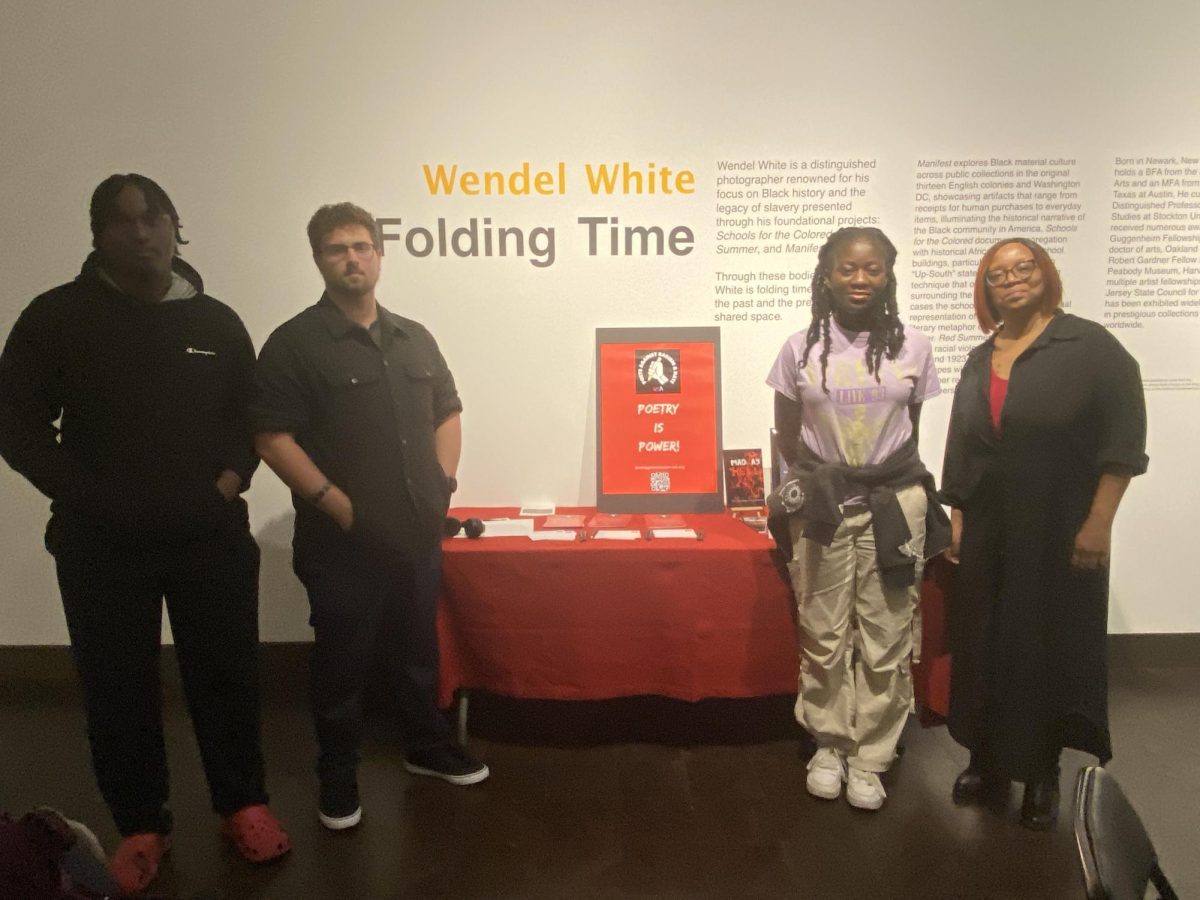

!["Between poems, owner of Words Matter Bookstore and host Keryl Hausmann spoke, saying 'To listen to [poetry] is different than to read it.'" - Graphics Editor / Brendan Cohen](https://thewhitonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/IMG_0653.png)